Adam Smith (1723–90) is a mystery in a puzzle wrapped in an enigma. The mystery is the enormous and unprecedented gap between Smith’s exalted reputation and the reality of his dubious contribution to economic thought.

Smith’s reputation almost blinds the sun. From shortly after his own day until very recently, he was thought to have created the science of economics virtually de novo. He was universally hailed as the Founding Father. Books on the history of economic thought, after a few well-deserved sneers at the mercantilists and a nod to the physiocrats, would invariably start with Smith as the creator of the discipline of economics. Any errors he made were understandably excused as the inevitable flaws of any great pioneer...

[B]usinessmen and free market advocates have long hailed Adam Smith as their patron saint... On the other hand, Marxists, with somewhat more justice, hail Smith as the ultimate inspiration of their own Founding Father, Karl Marx...

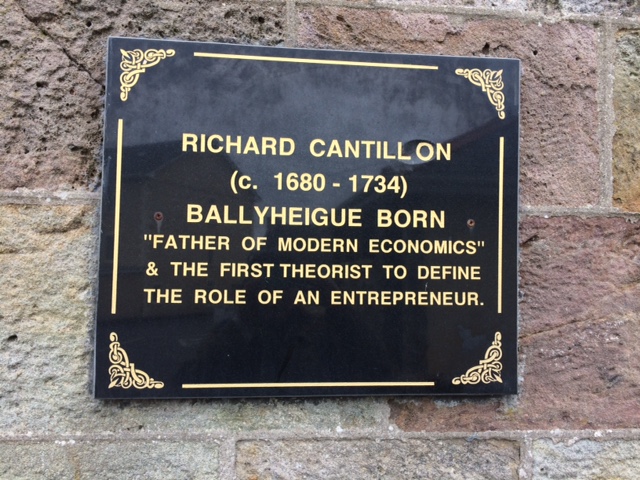

As we have already seen, Smith was scarcely the founder of economic science, a science which existed since the medieval scholastics and, in its modern form, since Richard Cantillon. But what the German economists used to call, in a narrower connection,

Das AdamSmithProblem, is much more severe than that. For the problem is not simply that Smith was not the founder of economics.

The problem is that he originated nothing that was true, and that whatever he originated was wrong; that, even in an age that had fewer citations or footnotes than our own, Adam Smith was a shameless plagiarist, acknowledging little or nothing and stealing large chunks, for example, from Cantillon. Far worse was Smith’s complete failure to cite or acknowledge his beloved mentor Francis Hutcheson, from whom he derived most of his ideas as well as the organization of his economic and moral philosophy lectures...

Smith not only contributed nothing of value to economic thought; his economics was a grave deterioration from his predecessors: from Cantillon, from Turgot, from his teacher Hutcheson, from the Spanish scholastics, even oddly enough from his own previous works, such as the

Lectures on Jurisprudence (unpublished, 1762–63, 1766) and the

Theory of Moral Sentiments (1759).

The mystery of Adam Smith, then, is the immense gap between a monstrously overinflated reputation and the dismal reality. But the problem is worse than that; for it is not just that Smith’s

Wealth of Nations has had a terribly overblown reputation from his day to ours. The problem is that the

Wealth of Nations was somehow able to blind all men, economists and laymen alike, to the very knowledge that other economists, let alone better ones, had existed and written before 1776.

The Wealth of Nations exerted such a colossal impact on the world that all knowledge of previous economists was blotted out, hence Smith’s reputation as Founding Father.

~ Murray Rothbard,

An Austrian Perspective on the History of Economic Thought, Vol. I, Chapter 16, "

The celebrated Adam Smith," 1995